A sermon preached at St Luke’s Maylands and St Patrick’s Mt Lawley 27th September 2020

The question before us this morning is the lawyer’s question: What must I do to inherit eternal life? I can’t say it’s a question I am often asked. The idea is outmoded. It sounds like wishful thinking for the weak-minded. It could even be a ‘no, no’ in terms of political correctness, for it might suggest some will achieve it and some not. In our culture of equality that would be unthinkable. In Jesus’ time it was a hot topic. It was assumed that some would make it, others not. This was not the only time Jesus was asked the question.

About 3000 Australians die by their own hands every year. The number is way more than the number of Covid 19 deaths. Suicide is the leading cause of death amongst young Australians. Much is being done to understand and tackle the problem and that is good! But I wonder has anyone thought that if our education system ignores even the possibility of God, and teaches our kids they are nothing more than intelligent animals in a purposeless universe – and if life becomes unbearable and you can see no hope, then putting yourself to sleep is a logical thing to do. It’s what we do to dogs and cats when they are suffering, why not me.

I start there just to point out that all is not well in our brave new world. There are questions which cannot be discussed, which should be discussed. In our heaven-on-earth society some are experiencing hell, and our schools may unwittingly be programming some to take the easy way out.

There are many reasons why we are confident that eternal life is real. The evidences of God’s creative hand and goodness are everywhere, and we do not believe he would make creatures with a sense of eternity and leave them forever frustrated. But the crux of the case is that when they killed Jesus, he didn’t say dead. Over the past two hundred years massive amounts of investigation and writing has gone into disproving this, but It has not succeeded. From a historian’s point of view the evidence rests on the independent testimony of five witnesses who wrote what they knew, and many others whose testimony is imbedded in these writing. There is also impressive circumstantial evidence. That is a lot for something that happened two thousand years ago. Existentially, certainty is added by the very real experience of millions who have encountered God through Jesus. I wish I had time to say more, but I want to get into the scripture before us. My starting point is the affirmation that eternity is real and eternal life in reach. The lawyer’s question is important.

Jesus points him to the law of Moses. The subject before us this morning is what the theologians call ‘law and grace’.

And behold, a lawyer stood up to put him to the test, saying, “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” Luke 10.25

What sort of answer did this lawyer expect from Jesus? Luke says he wanted to test him. Perhaps he was setting a trap, hoping Jesus would speak against Moses, and get him into trouble. In that case it doesn’t work. Jesus points right at Moses. ‘What are the commandments?’ The lawyer summarizes them. ‘Good,’ says Jesus. ‘Then you know the answer to your question: keep the commandments and you will live.’ Alternatively, he may have wanted to see how clever Jesus was, to judge his competence as a teacher of the things of God. As the story unfolds you get the feeling there is a genuine enquiry underlying the question. If this is the case, the lawyer doesn’t expect Jesus to point away from Moses. Every Jew knew that keeping God’s law was the way to life. So perhaps what the lawyer is expecting is that the rabbi Jesus will give his special take on the commandments: ‘Focus on this commandment,’ or that. ‘Be careful to recite the shema each day!’ ‘End each day with a prayer!’. That is what you would expect of a rabbi. But Jesus doesn’t go down that road either:

‘What is written in the Law? How do you read it?’ And he said to him, “You have answered correctly; do this, and you will live.” Luke 10.26-27

If you know your Bible, this will surprise you. For this is exactly what Paul says over and over will not lead you to eternal life. Do Jesus and Paul contradict each other? Some think yes, but Jesus himself contradicts what he says here. In the parable of the Pharisee and the Tax-collector in the Temple it was not the law-keeping man who found life, but the one who broke the law. So, is there a contradiction even in Luke? Or is Jesus playing a game?

Jesus has approved the lawyer’s summary of the law: ‘Love God with all your strength and love your neighbour as yourself’: this is the essence of the law which leads to life. But the lawyer comes back at him: ‘Who then is my neighbour?’ The next sentence is critical for our understanding. Luke says he wanted to justify himself. He wanted to be able to say, ‘Yes, I agree with you, and I have done it. I am in.’

So, Jesus tells his Parable of the Good Samaritan. We need to think hard about this parable. It seems pretty straightforward on the surface, but it has a colourful and controversial history. Students of the parables learn that in the early church there was a tendency to treat them as allegories. The most famous is Augustine’s interpretation of the Good Samaritan. The man who fell among thieves is Adam, and his descent from Jerusalem to Jericho is the Fall. The thieves are the Devil, who rob him of his immortality. The priest and Levite stand for the law which cannot save. The Samaritan is the Lord Jesus, who brings forgiveness. The inn to which he takes him is the church, and the innkeeper is St Paul. I have even heard the two coins identified with baptism and the Lord’s Supper, though I doubt that was Augustine.

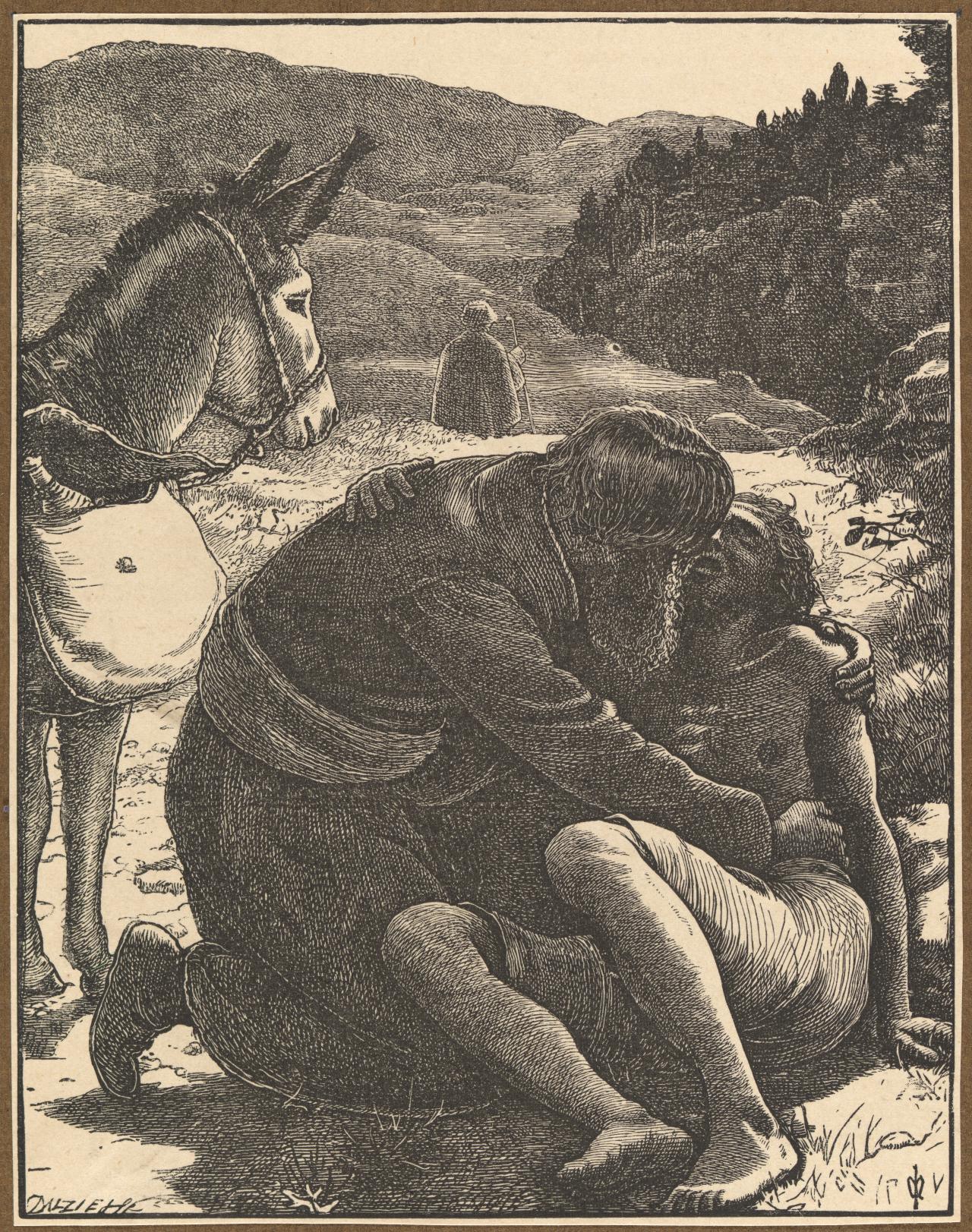

This imaginative way of looking at parables was discredited in a book on the parables written by Adolf Jülicher in 1888. How could Jesus possibly have meant this, when no one who heard him could have taken the parable that way? The interpretation is much more straightforward. The two representatives of ‘the church’ – to update things a little – are unwilling to stop; fear or distaste or urgency to get on with their own journey mean they cross to the other side of the road and pass by. We understand their reaction because we have all done it. The rabbis even discussed such a case. They debated what a Jewish person’s obligation was towards a heretic or a person who had a questionable occupation: Should you pull them up, if they fell into a pit. There was agreement that you should not push them, but some said the right thing to do was not to help them out. That would encourage godlessness. And now, along comes this Samaritan heretic and takes pity on the wounded traveler. He bandages his wounds, puts him on his donkey, takes him to an inn, and leaves the innkeeper with instructions to look after him. He even promises to pay for any further costs. ‘Who do you think became a neighbour to him?’ Jesus asks. The answer is obvious. Do we think the priest would have passed by if he saw it was his next-door neighbour in the ditch? Would you pass by, if you recognized the person in trouble as a personal friend? But Jesus throws out the boundary of our circle of those we should help. ‘Go and do likewise!’

What should a Christian be like? Here is a picture which has inspired all manner of merciful acts for two thousand years. Don’t try to limit the number of people you are obligated to help; treat as a neighbour anyone who comes your way, who needs your help – even your enemy. Even go looking for someone to whom you may become a neighbour. This is bedrock. This is the Christian way. We are on a journey and every one of us will meet people along the way we can help – or pass by on the other side.

But now I run into the problem that I have so often failed. My life is littered with painful memories of people I should have helped, and didn’t. I love the Lord Jesus and want to serve him. I love this parable. It is so good. And yet in situation after situation through busy-ness, laziness, tiredness, fear, or selfishness I find myself passing by on the other side. If this is what it means to love God and love my neighbour as myself – if this is what I must do to inherit eternal life – then I have failed, and, with the best will in the world, I go on failing. I can only speak for me, but the parable shows me what is good and right, and I feel more and more guilty.

What then should I do? Try harder? Yes, but I have been around long enough to know I will fail again. Has Jesus set the bar too high? At this point I start to get suspicious of the parable. Who really is like this? Who in their right mind would pick up an unconscious stranger from the side of the road, put her in your car, take her to a motel, pay for her accommodation, and effectively leave a blank check for her further care? I wouldn’t, and I don’t know anyone who would. The only person I know who is that good is Jean Valjean in Les Miserables. A wonderful story, but as I read it I found myself thinking over and over, ‘I am not like that. I wouldn’t do that; I couldn’t.’ Yet all through I was thinking this man is good. This man is better than any man I have known. But, of course, Jean Valjean is a fictional character; perhaps Victor Hugo is picturing Christ, or an ideal Christian.

This thought takes me back to the parable, and to wondering whether Augustine could possibly have been on the right track. The only one we know who has ever consistently acted in the way of the Samaritan is the Lord Jesus himself. Not that those who heard him speak could understand him this way, nor did he wish them to. The lawyer wanted to know how to get eternal life. Jesus told him to keep the two great commandments: Love God, and love your neighbour as yourself. ‘Do this and you will live!’ But he wanted to justify himself, so asked, ‘Who then is my neighbour?’ Jesus then paints this magnificent picture of what it means to love your neighbour as yourself. In doing so he destroys any possibility of the lawyer justifying himself. We need to see that. He makes it impossible for any of us to justify ourselves. He puts a question mark over whether we will ever be good enough to inherit eternal life.

Justification is something we usually associate with Paul. Justifying ourselves before God is something we cannot do, says Paul. We can only plead for mercy and trust God to do for us, what we cannot do for ourselves.

If Jesus is in any way moving in this direction, I want to suggest that as well as aspiring to be good Samaritans – all of us should – we should also recognize that, if we were painting the scene and wanted to put ourselves somewhere in the picture, we would not paint our face on the Samaritan, but on the one who fell among thieves. I don’t think Augustine was leading us up the garden path. Jesus is the one who saw us in our desperate state and did not pass by; who stopped and bound up our wounds; who placed us on his own donkey. The preacher – I don’t know who he was – who saw the donkey as Jesus’ human nature, was fanciful, but not so far from the spirit of the parable. Jesus became human to rescue us, to carry us on his own back … so that we may have eternal life.

I need to point out something else in Luke which will confirm we are not off the track in our reflections. His very next story is about two sisters, Mary and Martha, who welcome Jesus into their home. Martha does as we would expect: she sets about preparing a meal for the special guest. Hospitality was a cardinal virtue amongst the first Christians. Martha is doing as she should, she is loving her neighbour – in practice. What about Mary? She is in the loungeroom sitting at Jesus’ feet, wrapped in what he is saying, and oblivious to everything else. Martha is understandably stressed to be left on her own. ‘Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to serve alone. Tell her to help me!’ ‘Tell her to get off her butt and love her neighbour!’ That’s what she was thinking, anyway. ‘Tell her to keep the law!’ Jesus does not argue with that; but he points to something different: Mary is basking in the presence of the Lord, feasting on the words of the King. This, says Jesus, is the one thing that is necessary; this is eternal life. It will not be taken away from her.

So, Luke’s answer to this old problem of law and grace, and it is Jesus’ answer too, it that the law stands as the way to life. The law is God’s revelation of the good life. ‘Do this and you will live!’ But Jesus, has come, disguised as a Samaritan heretic, to seek and to save the lost along the way; to be a physician to the wounded who need a doctor. And he turns out to be the Christ, the promised King. To be in the care of the King – to dine with him like the disqualified tax-collectors and sinners – is to be in his kingdom, to be enjoying eternal life now. Eternal life is not just life that goes on and on; it is the life of the future aeon, the kingdom of God, which begins when I person starts to trust Jesus. Mary was enjoying eternal life – the life of the kingdom of God. Luke depicts her as the model disciple. He invites us all to join her at Jesus’ feet in the enjoyment of eternal life, now and for all eternity.