Luke 7.11-17

The fifth talk in a series, The Man they Crucified, given at Kalbarri Anglican Church 5th November 2023

Last time I showed some of the reasons we can be confident that Jesus really did do miracles. These show that he came from God, as he claimed. Today I want us to think about the nature of his miracles. What sort of miracles did he do? Luke records an incident that shows us the sort of miracles he didn’t do (9.51–56).

He was traveling on foot to Jerusalem, and sent two of his followers into a small Samaritan town to arrange a place to stay; they returned saying the Samaritans would not welcome them; Jews and Samaritans didn’t get on. James and John were known as the “Thunder-boys”; you can guess what they were like. They asked Jesus to let them call down fire from the sky and torch them. Many years ago, he prophet Elijah had done something similar, so it seemed an obvious move. (2 Kings 1) Jesus rebuked them, and they continued their journey. The remarkable thing about this incident is that Jesus reprimands two of the most prominent leaders of the early church. Clearly the story wasn’t made up; the first Christians didn’t make up stories to put their leaders in a bad light. So, if they did suggest this, did they really think Jesus could have given them power to do it? Obviously they did. They had seen Jesus do miracles, and on one occasion he had empowered them; it seemed like a reasonable thing. But none of Jesus miracles was done to harm anyone, which would have been a surprise even to his folowers, considering that in the ancient world anyone thought to have magical powers was expected to use them against their enemies. It is the same in Africa today. The feelings between Jews and Samaritans were not unlike those between Jews and Palestinians today. Calling fire from heaven would seem like a sensible thing to do—if you could. But no, most of Jesus’ miracles were done to heal or help; not a single one was to harm anyone—though there were many who wished to harm him.

We learned about how Jesus healed the servant-son of a military officer. The officer recognized Jesus’ authority and leaned on it. He understood that Jesus had divine authority to command anything. We ended with a question: If God gave Jesus the power and authority to heal, and more, why doesn’t he heal today? He does, of course, again and again, but not always, and not often in that miraculous way we would like to see.

And there are bigger problems than our sicknesses: the world is full of violence and suffering, some of it natural, and some caused by us. We seem to be living in the age of continual crisis. What horrifies me most is when people, especially children, are buried alive. And it is happening every day in Gaza. I wonder how my faith would last, if I were entombed alive.

Some have ceased to believe there could be a God. They cannot reconcile the horror with the existence of a loving and powerful creator. The internet is awash with atheist propaganda, so the idea is constantly dangled before us. What bothers me more than the atheists, is the unknown number of others, who are less certain than they once would have been. When God treats them well, they believe, but when things go pear-shaped they doubt, or disbelieve altogether.

Most atheist propaganda is illogical and false. The universe demands that someone or something brought it into existence. But the atheists appeal to the prevalence of evil and suffering is a powerful argument, even when a more logical conclusion would be that God doesn’t care, as Epicurus taught. Why should he? Do we care, when we wipe up ants in the kitchen?

One night I was fishing with my uncle about twelve kilometers off the coast. He pointed to the stars and said, “You can’t be out here night after night and not believe there is a God. But I don’t believe he cares about me.” His eldest son had cerebral palsy and died in his twenties; his second son died as an infant.

He is there, but does he care? Does he even see? Does he feel anything towards the suffering of human beings? Or is he unable to do anything? There is hardly any more important question we humans can ask. Do we live in a crazy, world-size, concentration camp, where any of us is likely at any time to be taken and slaughtered on somebody’s whim, or is there light at the end of the tunnel—some hope?

Christians believe in God primarily because of Jesus. We are convinced that Jesus came from God, and spoke for God—among other things because of the miracles. It was witnessing these things that brought Jesus followers step by step to certainty. But also, Jesus was good and compassionate; that is why we believe it must be the case with God.

Something unexpected happened one day when Jesus traveled to the small Galilean city of Nain, which confirms that God is good. How a person reacts when they are off-guard tells you a lot about them. Some of you will remember back to when Bob Hawke was Prime Minister of this country. He was giving a speech, live, on television, and one of those studio bulbs exploded like a gunshot. The Prime Minister blasphemed horribly and everyone in the country heard it. It cost him.

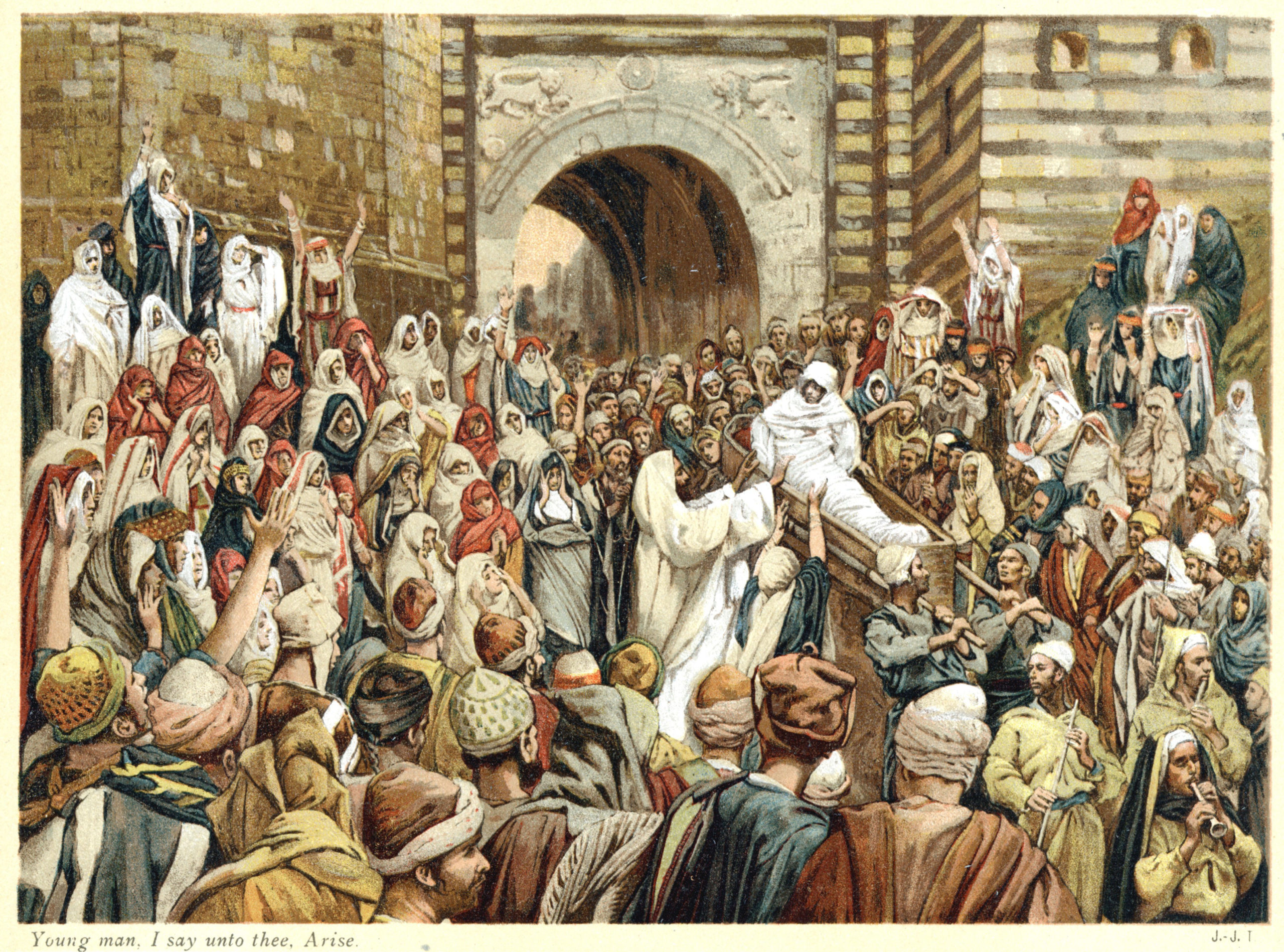

A great crowd of onlookers accompanied Jesus on this cross-country walk to Nain. It was his first trip there, and people wanted to see if he would do things like he did in Capernaum. They must have been glad to catch sight of the town walls. Inside was food and rest—at least that is what they thought. In fact, they had no way of knowing what was inside. The only way in was the town gate, and, unbeknown to them a funeral procession was approaching from inside. They met unexpectedly at the gate.

Funerals are very private. In a small town, when a funeral passes, you stand still, remove your hat, and look serious until its gone; the last thing you want is to get involved. But Jesus was staring and obviously interested—he was trying to figure it out. An open box on the shoulders of four men. Nothing out of the ordinary there, that was the way they did it. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of grief; that is odd. A small group of women are wailing in the traditional way: respectful, conventional. Only one person really seems upset: a women in her late twenties. No husband around—perhaps he is in the box. No children, either; could it be a child?

Whatever it is, this woman’s only loved one has just died—her grief is severe—and Luke tells us that Jesus was filled with compassion.

Compassion is the pain you feel at someone else’s suffering. It’s not a feeling we particularly welcome—not in the real. When we’re comfortable in front of the television we revel in it, for there’s no danger of us getting involved.

I can remember occasions when I felt compassion, but switched it off, because it threatened to get me involved. One time when I was driving, I saw someone attack a boy and knock him off his bicycle. I should have gone to help him, but it was a dangerous area. I turned off my compassion and drove on. I am not proud of it.

Luke tells us Jesus was moved with compassion; he also got involved. At the end of the story people were saying to each other: “God has visited his people.” If it is true that God came among us in the person of Jesus, then God was moved with compassion. And if God was moved with compassion at the sufferings of that woman, then could it be he is moved with compassion at all our human sufferings?

Could God suffer the sufferings of eight billion people? Yet the Old Testament says, “In all their afflictions he was afflicted.” (Isaiah 63) He is speaking about Israel, but Jesus teaches that his love goes out to the world. God is a compassionate God: that is the first great truth we learn from this story.

But this raises the question we asked before: why doesn’t he step in and call a cease-fire in Gaza, for example? Some years back a Jewish rabbi wrote a book on suffering. Of course, he was thinking of the six million Jews who died in Hitler’s extermination camps. God would like to help, he says—he does feel compassion, but there are limits to his power. Sometimes he just can’t help. Jesus would not have agreed with that. The power of the God who made heaven and earth by a word of command, and led Israel out of Egypt through the sea is not limited.

Jesus walked into the road and stopped the procession! Imagine that?

He’s telling the men to put the coffin down. What were they thinking?

He’s looking into the coffin. The crowd has frozen solid. He sees a teenage boy and it tells him the whole story: husband dead, now her only son—no wonder she is suffering.

So, he turns to the woman and tells her not to cry. And he turns back to the coffin and says, “Young man, get up.”

Luke tells us the young man sat up, and Jesus gave him back to his mother. He does have power; even power to raise the dead. And, if he can raise the dead, there is no suffering he cannot deal with.

The second thing we learn from this story is that the compassionate God, has power to deal with suffering. Jesus proved it in the most marvelous way.

The people were thunderstruck: “A great prophet has arisen among us! God has visited his people.” God visited his people in the person of Jesus, with authority, and compassion, and power. So why doesn’t he act today?

One reason is that we sent him away. The world didn’t want him, and still doesn’t. He has said he will not return until Israel at least wants to welcome him But that is not the full story. The Gospels give us another clue: when his only Son was dying, God did nothing.

Do you think he didn’t feel compassion when Jesus was stripped and flogged and mocked and spat at and nailed with iron spikes through his wrists and ankles, and suspended in agonizing torture for seven to eight hours? Why didn’t Jesus do a miracle then; the onlookers urged him to? Why did God look on and do nothing?

The answer, I think, must be another compassion: God’s burning compassion for a suffering and dying world. “He does not willingly afflict or grieve the son of men,” said Jeremiah when Jerusalem was in the midst of its own Gaza-experience. (Lamentations 3.33) And St John says, “God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son ….” Gave him up—that means, let him die in agony.

The answer to why God allows suffering must lie in his plan to rescue the world, and the end of that story has not yet been told. Jesus announced a new world: the kingdom of God. It hasn’t come yet—not in its fulness—but it will. When we believe in Jesus we are believing in his promise of a new world. To bring it in he must remove not only the suffering, but also the evil and sin that is the root of the suffering. And that evil is in all of us. It was to make atonement for the sins of the world that Jesus died on the cross. His resurrection was the next step in the coming-to-life-again of all his people. The raising of the boy at Nain was proof that he had power to deal with death, and will one day usher in the new world he proclaimed. But the question of who will possess God’s kingdom remains unanswered. Jews and Palestinians are literally at each other’s throats today to own the land of Palestine, and inherit Abraham’s promise. The New Testament makes it plain that God’s promise to Abraham ultimately entails the whole world—the cosmos even—and will not be fulfilled until Jesus returns to make all things new. In the meantime, God’s Spirit is at work bringing people from every nation to follow the king and be part of his kingdom.

None of us can escape suffering. It is not a question of “Whether?” but “When?” We all hope we will die later rather than sooner, and without suffering, if possible. But that is hardly the point. It is death itself which is the great evil, and what can God do about that?

As he hung dying on the cross, the man next to him twisted his head towards Jesus and whispered, “Jesus, remember me when you come in your kingdom.” And Jesus had compassion for that dying man. “Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise.” The terrorist acknowledged Jesus as his king, and Jesus welcomed him into his kingdom. So, put your trust in Jesus, and when you die his invisible presence will come to you and order your spirit to live, and take you into his presence in paradise. That is his promise.

But it is not just about me. The world is straining—suffering—towards a face-to-face confrontation with its creator, and the renewal, which is its destiny. Jesus promised that when he comes again, he will raise the dead, save his people through the great judgement, and make the world a place of life. “The hour is coming,” he said, “when even those who are in their graves will hear his voice. Those who have done good will rise to life; those who have done evil will rise to be condemned.” So, one day the Lord Jesus will come even to your resting place, and say, “Young man, Young woman, Child, Old man, Old woman, Get up!” And you will. What happened at the gate of Nain proves it.