Luke 19.11–27

A sermon preached at Christ Church Midrand 30th June 2024

Roydon Frost, the Rector of Christ Church Midrand in Johannesburg asked if I could speak to the theme of their mission week: “But this is not the Jesus I ordered.”

You may have watched the wedding of Harry and Megan. The preacher talked a lot about love. He didn’t say much about Jesus, but I suppose if you’d asked him he’d have said Jesus taught us to love one another. He did! The last of my daughters married soon afterwards. She flew from Canberra where she lives, to Perth, where Lorraine and I live, to organize the wedding. I recommended a church, and she went for an interview with the minister. Mark, she said, I don’t want a sermon about love. Please talk about Jesus. Why did she say that? I guess she felt love had been overdone, and that Jesus was being short-changed. There is much more to Jesus that a teacher of love.

On Friday I gave two talks in Mauritius on Jesus’ parables. Each of the parables is like a window into Jesus’ mind. One I looked at was the Parable of the Pounds; you would be better to call it the Parable of the Returning Nobleman. A prince goes away to a faraway country to be made a king. Before he left he gave amounts of money to ten of his servants to do business for him. When he returned he called them in and asked them what they had earned. Some he rewarded, but one, who had done nothing with his money—he hadn’t lost anything, just put the money away, and returned it in full—he got a blasting for being so useless. The king took his money back, and gave it to the chap who had made the most profit. Then he gave orders to round up all his enemies and execute them: “As for these enemies who did not want me to rule over them, bring them here and slaughter them before me.” That’s how the parable ends. A bit rough, don’t you think, and hardly very loving! But if this is showing us another side of Jesus, we should look at it.

Jesus told lots of parables. It was the way he thought and taught. It’s pretty obvious in this one that he was talking about himself: he is the prince who was made a king—which has been a problem for many interpreters, because Jesus likens himself here to a well-known villain and cut-throat businessman: “You take up what you did not lay down; you harvest what you did not plant.” Twice Jesus describes himself this way. And then there are those terrible words at the end: “Come and slaughter them before me.” People don’t like to think of Jesus like that. I don’t.

Herod was the king who tried to have Jesus killed when he was a baby. He is known in history as Herod the Great because of his long rule over the Jews and many great buildings, some of which are still standing. He died when Jesus was a toddler. Each of his three sons wanted to succeed him as king, but Israel was part of the Roman empire, so Herod’s will had to be read before the emperor and ratified. Each of the sons caught a ship to Rome to argue their case. Also, a Jewish delegation was sent to argue for self-rule; they didn’t want any more of the Herod family ruling them.

The eldest son, Archelaus, came home not as king exactly, but as the ruler of Judaea and Samaria> He was titled “ethnarch,” but was king as far as the Jews were concerned. On his arriveal he proceeded to settle scores. He was a total failure as a king—a monster in fact, and in time the Romans realized their mistake and sent him into exile. All this was recent history, so everyone who heard Jesus’ parable knew exactly who he was comparing himself with. But what is he doing likening himself to a notorious scoundrel? As I said, people don’t like to think of Jesus this way, but this is how he pictures himself.

Scholars once questioned whether Jesus taught everything the Bible says about him. Whatever view you might have of this, one thing you can be sure of: no Christian would ever have made up this comparison. Only Jesus could have done it. This is authentic Jesus, and it’s not untypical. Jesus could hold a crowd in the open air all day. He must have been one of the world’s greatest story-tellers. Some of his parables rely on a shock element. You didn’t go to sleep when he was preaching. He means us to be offended by this parable; we are meant to protest. What is he doing likening himself to a murderous tyrant? How is he like him? When you start asking questions, he has hooked you.

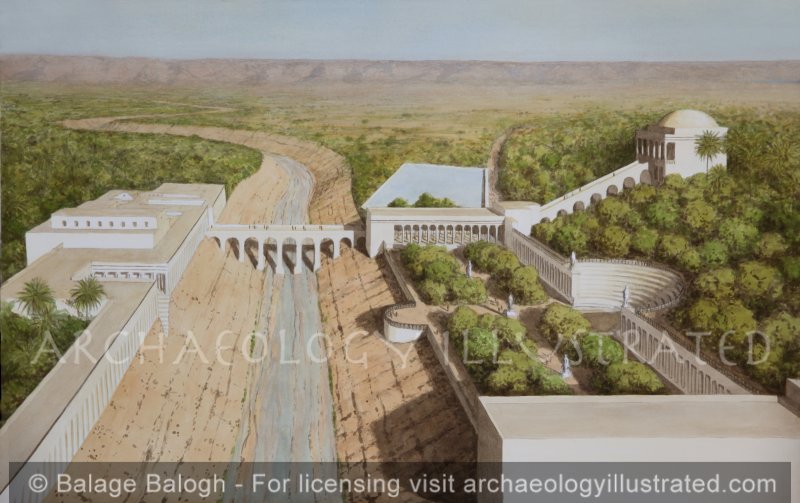

An interesting thing about this parable is that we know the place where it was told, and the time. Apart from when he taught in Jerusalem, this is the only parable that we know where and when he said it. It was Jericho, a week before his death. Archelaus had built a huge palace near Jericho; you can still see its ruins today. It was probably in view when Jesus told this story, and may have been what brought Archelaus into his mind.

So what’s it about? Luke tells why Jesus told it: the crowds were thinking that when he reached Jerusalem—only a day’s walk away—tomorrow in other words—the kingdom of God would appear. They were excited. Jesus had spoken a lot about the kingdom of God, and for them that meant the revival of the ancient Jewish kingdom built by David (read 1 and 2 Samuel). The crowds thought that when they came to Jerusalem Jesus would declare himself as king and take over the government. If he could feed five thousand people in the wilderness, and still a storm, and raise the dead, it shouldn’t be any trouble for him to topple Israel’s corrupt leadership and make himself king. His followers once asked him to call down fire from heaven, so cleaning up the opposition in Jerusalem shouldn’t be a problem. But no, that’s not the way it would be. He would need first to go into a distant country to receive his kingship, and then return. He was talking about heaven. He knew he would be killed within the week; he wasn’t going to defend himself. But he knew he would return.

We need to pause here and scratch our heads.

At present there is a war going on in Israel and Gaza. Israel and Rome were not at war when Jesus spoke this parable, but he warned that they soon would be, and it happened as he said. It was a war that lasted five years, and a lot more children died than have died in Gaza. If Jesus had taken over, he could have stopped that war. I guess he could also stop the war between Israel and Hamas. But he let himself be killed. Why, why, why?

We know the answer. The Bible tells us. In Paul’s words he was reconciling the world to himself, not counting our sins against us.[1] Think about it! He regarded securing our forgiveness as more important than saving the lives of all the children of Gaza. Shocking, but you will never understand Jesus until you see that this is true. I will have more to say about this later, but let’s go back to the parable.

The citizens sent a delegation to Augustus: “We don’t want this man to rule over us.” And Israel rejected Jesus as its king—the world still will have none of him. On his part, he would not take up arms against them (or us); he let us do our worst, and trusted God to bring him back in his good time. That will be the greatest come-back ever.

Mainly, when we think of Jesus’ second coming, we think of salvation, and that is correct. Jesus’ “gospel” was mainly about salvation. He will return to rescue his people from all their troubles, resurrect the dead, liberate his creation from decay, and abolish death for ever. But when he comes, he will also judge the world, and abolish all evil from the universe.

Paul says God “has set a day to judge the world, by the man he has appointed, and has given us assurance of this by raising him from the dead.”[2] It is a no brainer, of course, that sooner or later God must judge us. If he is any sort of a God—that sounds silly; what I mean is that, if he is good, and if the world is his, and he rules it, he must sooner or later sort out the mess it has fallen into. Good and evil must be seen for what they are and have their reward. What is true must be seen to be true, and what is false shown up. If you knew nothing else about God, you would know that in the end he will say, “Yes, this is true and this is false; this was good; this was bad.” This is how it will have to be—if God is God. The surprise is that he has waited so long, and that he has appointed a human being—one of us—to do the judging. If you knew you were to be judged, who would you rather be judged by, than the man who touched lepers, forgave a sinful woman, and healed the blind?

But judgement is scary. I mean, the enemies of God will be destroyed. There is no other way to read this parable. In the end, God will not share his universe with enemies. Why not? Because sooner or later they would destroy it! If God does not restrain things, Russia and America and Germany and Ukraine, China and Taiwan and Korea and Australia, Israel and Iran and Hamas and Hezbollah and Yemen—and Africa wont escape—I am not trying to take sides or lay blame; I am simply saying that the world is on its way to self-destruction. That is where our rebelling and turning away from God has got us. God has let it go on for a time, but evil will not triumph forever. There will come a time for judgement, and unless we want it all to happen again, God will destroy his enemies; he must. That is what Jesus is trying to get through to us when he says, “Bring these enemies of mine and kill them.”

Who are these enemies? Well, no one who resists God’s right to rule his world, no one who ignores his law, no one who rejects his king, and hurts his fellow human beings, will have a place in the new world that is coming. And honestly, this accounts for all of us. We are created by him, and everything we have comes from him, so if we go on ignoring him, or refusing his right to rule us, we are enemies. And unless there is a miracle of forgiveness and transformation we will all go done. That is why Jesus chose the cross: as Paul says again, “He became sin, who knew no sin, that in him we might become the righteousness of God.”[3]Jesus’ plan is to populate the new world—the kingdom he is building—with a renewed people: forgiven, spiritually transformed, and cured of their sin, which includes being taught to love! That is why the kingdom didn’t appear immediately, and why the war in Gaza goes on. Jesus is building a new world, and we are each invited to participate. There is so little love in this world —so much hate and indifference. But one day there will be a world where people look out for each other, though it is still a long way away. For now, Jesus offers us forgiveness, his Holy Spirit, and eternal life—he also begins to show us how to love—but if we reject his offer, then all that is left is eternal death, whatever that may be. So, Jesus wants people to know that judgement will be no less severe than when Archelaus slaughtered his enemies. That is part of what this parable is about. But there is more.

There will also be judgement for God’s forgiven children. This is something we don’t often talk about. But when the nobleman returned, he wanted to know what his servants had done in his absence. When Jesus returns he will want to know what we have done while he was away.

But aren’t we promised that if we believe in Jesus we won’t be judged? This is true; Jesus himself said, “Whoever hears my words and believes in him who sent me … does not come into judgement, but has passed from death to life.” But what he is talking about is the judgement that brings condemnation. When we trust in Jesus, he forgives all our sins, past, present, and future; we are not condemned, now or ever; amnesty is ours. This is why he will die, before he returns as king—to make all this possible. The king carried the guilt of his people, and paid it out. Believers don’t need to worry about being condemned, but that doesn’t mean our whole life will not be displayed for the whole universe to see. There will be nothing swept under the carpet when Jesus judges even our secret thoughts.

It’s significant, I think, that the question put by the returning king to his servants is not, “Did you do what I told you?” but “What did you do with what I gave you?”

We are stewards, you see—managers of God’s gifts. And the lives of God’s children will be judged, not to condemn them, but more to reward them. And Jesus indicates that the rewards will be great—much greater than anything we deserve. “You used the money I gave you to make ten times as much; take control of ten cities.” The only sad Christian that day was the chap who had done nothing with what the Lord gave him. God’s gifts are to be used, not sat on.

What are those gifts? Not just our money, though that is important—we can do a lot with our money for good or for evil. But there is also our time, our abilities, our opportunities, our education, our energy, our experience—there is no end to it. Everything we have is God’s gift, and he asks us to use it well. “Trade with it until I return!” In another place Jesus tells us that even our prayers bear fruit. I guess we won’t know what our prayers achieved until Jesus returns. Not only will we tell him what we have done; he will tell us things we achieved we knew nothing of.

I am not sure about this last guy. Was he a fruitless believer or an enemy? Jesus says in John 15: that if we remain in the vine—he is the vine, we are the branches—we will bear much fruit. We will bear much fruit. It is a promise not a demand. Every branch that does not bear fruit will be cut away and cast into the fire. So I think the last man is actually a warning: use what God has given you. He is not there to answer our questions about who will and wont be saved.

So, what does Jesus mean us to learn from this parable? First that he is judge of the living and the dead. Second, we will all face judgement which will be final for those who refuse to acknowledge his kingship. He told the parable when he did to warn that he must depart before returning as king. That he will certainly return is the third thing. God raised him from death to give us assurance of this. He died to ensure his people would not be condemned. We are forgiven and free. But fourth comes the challenge, what are we going to do with what he has given us? What are you going to do with the rest of your life?

[1] 2 Corinthians 5.

[2] Acts 17.

[3] 2 Corinthians 5.