Hope Worth Having

Four sermons at St Matthews Shenton Park for Advent 2015

- Day Star

Mark 10.32-52

Two weeks ago we looked at the Old Testament’s promise of an ultimate comfort for Israel and the world. Last week we saw how John the Baptist prepared for the arrival of Israel’s promised king by warning the people that judgement was nearly on top of them. It was their last chance to turn to God and seek his mercy. John’s picture of the coming Messiah is drawn mainly in the colours of a fiery judgement.

We come this Sunday to the third sermon in our Advent series where we focus on the Lord Jesus himself. I looked for a single Scripture that might give us some insight into what he was really like and chose Mark 10.32-52. I want us to look at Jesus through the eyes of James and John.

By way of background I am reminded of the occasion where Jesus was refused entry into a Samaritan town. Outraged at this breach of hospitality, these two disciples asked Jesus if they could call fire down from heaven to torch the village off the map. Luke tells the story in 9.51-55. It must be true because Jesus rebuked them; the early church didn’t make up stories about Jesus rebuking their most honoured leaders. James was the first apostle to be martyred, and next to Peter, John was the best known of the disciples and one of Jesus’ closest companions. It is this John who wrote the fourth gospel.

These brothers had a nick name, Boanerges, “Sons of Thunder”. We can imagine the sort of men they must have been. The sort who might shoot up an abortion clinic, I suspect, if they thought they had right on their side. In the Jewish world of the first century such people were known as “zealots” and were respected, just as they are by many Muslims today. Today we would call them “radicals” or “fanatics”.

John had been a disciple of John the Baptist; maybe James had too. They knew that Messiah was coming to judge. He would burn the chaff with unquenchable fire. So why not get started with this unbelieving Samaritan town?

I am speculating a little, but angry men with a lot of hate in them, are attracted to struggle movements. Perhaps that is one reason so many disaffected young people are drawn today to Islam. Maybe the prospect of fighting is what attracts them. Of course the movement does its best to fan that hate to white heat – even sometimes to killing yourself if it will hurt the enemy.

Both these men followed Jesus because he said the kingdom of God was coming. This meant revolution – and a fiery judgement, as we have seen. They may have had some early misgivings about Jesus’ peaceful ways, but they were both there and saw Jesus turn shining white on the mountain of transfiguration, and talking with Moses and Elijah, so they knew for a fact that he was Messiah. Jesus might be concentrating now on gathering more followers, but sooner or later the revolution must begin because that was Messiah’s job. And what better place for the judgement to start than with this inhospitable Samaritan village? And how better than with fire from heaven?

The extraordinary thing about this story is the disciples’ obvious belief that they could have done it, if only Jesus would give his permission. It says a lot about the many acts of power they had seen. They had no doubts about his power. The incident says heaps about what sort of king they imagined Jesus would be.

What kind of king? That is the question I want us to ask this morning. There is an Ethiopian student in Cape Town doing PhD research on the Gospel of Mark. He is asking is what people’s expectations of the coming king would have been, and how Mark’s account of Jesus might have struck them when it was first written. In particular, he is looking at the way Jesus related to outcasts and people on the margins of society, and what that meant in terms of how he viewed himself status-wise.

What models did the Jews have to help them imagine what the future king would be like? David was the obvious one. Did David take notice of the sick and marginalized? Not really. He was a man of war who fought for his people’s freedom. When he burned with anger at Goliath mockery of Israel, David showed himself to be a true zealot as he advanced to kill the giant.

Jews had another hero they could measure the Messiah with. Judas Maccabaeus (“Judas the Hammer”) who fought a war to liberate them from the Greeks and then became their Prince. Was he known as one who took special notice of the poor? Listen to how the first book of Maccabees describes him.

1Mac. 3:1 Then … Judas, called Machabeus, rose up … and … fought with cheerfulness the battle of Israel. … 4 In his acts he was like a lion, and like a lion’s whelp roaring for his prey. 5 And he pursued the wicked and sought them out, and them that troubled his people he burnt with fire: 6 And his enemies were driven away for fear of him, and all the workers of iniquity were troubled: and salvation prospered in his hand. 7 And he grieved many kings, and made Jacob glad with his works, and his memory is blessed for ever. 8 And he went through the cities of Juda, and destroyed the wicked out of them, and turned away wrath from Israel.

Kingdoms are lost and won on the battlefield. There is no time for talking to beggars. So I think this student is onto something. We read the gospels, and Jesus’ avoidance of violence and frequent interactions with the blind and the crippled seem natural and to be expected, but were they then?

There is another later figure with whom I think it is important that we compare Jesus because his influence remains so great. I mean Muhammad, the prophet of Islam. According to his biographer, Ibn Ishaq, in his early career “He had simply been ordered to call men to God and to endure insult and forgive the insolent.” But then God gave him permission to fight – “fight until no believer is seduced from his religion (Islam) and until Allah alone is worshipped”. It was this which set Islam on its course down to our own time.

You may have heard the British Prime Minister this week speaking to the House of Commons calling calling Islam a great religion of peace. This is political correctness at its most blatant. Whatever else it is, Islam is not a religion of peace. What David Cameron should have said is that ISIS is hurting many millions of peace-loving Muslims. It is probably true that most Muslims are peace-loving people, but the religion itself is a call to war. The peace which it proclaims is the peace that will reign when the whole world has become Muslim and there are no infidels left.

Muslims often appeal to their right to defend themselves, and very few would quarrel with that. But Westerners are bewildered at how the jihadists have twisted things to convince themselves that they are under attack and defending themselves, when it is exactly the other way around. They are easily portrayed as crazy. But if you understand Muhammad’s permission to fight “until no believer is seduced from his religion”, you will see they are not mad. This permission means that Islam defines every non-believer as an enemy attacker. The secular West especially seduces people away from God and so is seen as a satanic enemy which must be fought “until Allah alone is worshipped”. In Islamic theology the world is divided into “the house of Islam” and “the house of war”.

Ibn Ishaq’s, Life of Muhammad,[1] Is nearly 700 pages long and almost 400 of them are about Muhammad’s battles. Even more than Christianity, Islam promotes the imitation of Muhammad, even his incidental characteristics, like wearing a beard. ISIS is simply imitating Muhammad. When the Jewish clan of Banu Qurayza surrendered after a 25 day siege, Muhammad imprisoned them in Medina, dug a great trench in the town square and beheaded all the men. Their families and possessions were divided among the Muslims. This was repeated over and over. I believe it is important today that we study and compare Jesus and Muhammad, because each is held out as a model of a new humanity. People may have to choose.

Come back to James and John as they approach Jesus with their special request. (Mark 10.35) Jesus has just indicated that he must go to Jerusalem and that when he does he will be rejected and killed – and then raised from the dead. None of the apostles seems to have known how to take this; it is too opposite to their own expectations to be taken literally. They know that things are coming to a head. Jerusalem – yes, it is time for the showdown. Struggle – yes, that must be. But he their Master is God’s Messiah and victory is assured. Perhaps they imagine he will use his miraculous powers at the last moment, overcome the unbelievers and take his rightful place as King. And that means setting up a new government. Jesus has already told Peter that he is to have some high office as “keeper of the keys” in his kingdom, so it is hardly surprising that the others are speculating about their places. “Grant us to sit one at your right hand and one at your left in your glory?” James and John want to be there in his cabinet as his chief advisors.

“You don’t know what you are asking,” Jesus replies.

I want to make a point here in passing that this is prayer that Jesus refused to answer. How many of our prayers would it be true of, that we don’t know what we are asking, and Jesus very mercifully does not grant them. We should see unanswered prayer not as God not caring, but as precious guidance. That is not the point of the passage, but in the long term it certainly provided important guidance to James and John. One of the very interesting things about the early Christian movement is that although they believed passionately in the kingdom of God, they had no interest in trying to displace the existing authorities, like Muhammad did in Medina. Read the early chapters of Acts with this in mind!

Jesus asks James and John whether they are able to drink the cup he must drink and be baptized with his baptism. They think he is asking whether they are willing to fight for him and suffer, and they say, yes. Jesus did not mean that, but he agrees with them that their time to suffer will come.

Then the other apostles get wind of the brothers’ attempt to get in before them and they are naturally angry. A row is brewing. Jesus calls them together and talks to them about roles and status in the kingdom of God.

The curious thing is that he doesn’t say that they shouldn’t wish to be great. Nor does he say they will not have positions of greatness in his kingdom. They will, but the determinations have already been made. Later he will tell them that they are to rule as kings over the twelve tribes of Israel. But what sort of rulers will they be? “ Those who seem to rule the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones push them down. People vie for positions of authority so they can lord it over those below them. The higher up you are the more people you can command to do what you want. Both the words Mark uses carry the feeling of pushing other people down. Power is intoxicating: the feeling that you are in control is good. But Jesus says it is an illusion. They only seem to rule. Look at the presidents and prime ministers who gathered this week in Paris to see how not in control they are: how much they are pushed and pulled by forces beyond themselves, even as they seek to impose their will.

But the real point Jesus wants to make is that in the kingdom of God authority, position, status – all these things are real – but they are for the purpose of serving those lower down the chain. We have a tradition of public service which is influenced by what Jesus says here, so we are not as struck by these words as we should be. But they must have turned the thinking of those who first heard them upside down. A ruler for the sake of those he rules? That is a strange notion.

Jesus uses himself as an example. “The Son of Man didn’t come to be served, but to serve.” And the particular form of his service is to give his life as a ransom for many.

This is familiar to some of you – perhaps not to others – that our great need is to be ransomed; that is how Jesus saw it. It is very much not how people see it today. This aspect of Christianity – and let’s be sure that the cross is the very heart of Christianity – has been under attack for a long time. Muhammad did not understand it and modern Muslims are contemptuous that anyone should be forgiven because of someone else’s sufferings. Western intellectuals have been hammering the idea of atonement for two centuries as primitive, unjust and illogical. It has been lampooned in recent times as “cosmic child abuse” even by someone who says he believes in the Bible. I once received a letter from the leadership of this diocese forbidding me to teach this doctrine. Many church scholars have argued that the idea of Jesus’ death being a ransom came from Mark and Paul, that Jesus would not have believed anything so gross.

Albert Schweitzer was no friend of Christianity, but he was clear on this point. Why would Jesus not have seen his death in sacrificial terms, he asked, at a time when hundreds of thousands of pilgrims were crowding into Jerusalem to offer their Passover sacrifices. Passover celebrated God’s redemption of his people from their slavery in Egypt and looked forward to a new redemption when he would finally release them from all oppression. Part of that original redemption involved each family sacrificing a lamb and painting its blood above their front door so the angel of death would “pass over” and spare their firstborn sons. Sacrifice was part of their everyday life and thought. Jesus’ words about giving himself as a ransom for many must have been breathtaking, and Schweitzer thought he was mistaken, but they would have been perfectly sensible to any Jew of his day. Schweitzer saw that clearly, even though he thought Jesus was deluded. But was he? We always assume that what we think as moderns is true, and that whatever our ancestors believed was superstition. But is that sensible?

Your modern intellectual views it as lunacy that anyone should need to be ransomed. Our thought world is about human rights. I have a right to life, a right to be treated equally under the law, a right to a free education, free health, employment,. In Norway you have a right to free recharges for your electric car. Ideally everything should be provided, and if God has the means, why does not give me what I want?

It begs the question, who should give me what I have a right to? Who owes me? The government, I suppose, but what happens if the government goes broke. If it is my right; someone should give it to me. Should I teach your child for free, if the government can no longer pay me? But if I owe you, shouldn’t you owe me? If it is my right to receive from others, surely it is their right to receive from me.

And what about God? Does he owe me, or do I owe him? The reality is he gives us life and health and happiness and a million other good things; what do we give him? The truth is we are hugely in his debt and have defaulted on the little he asks in terms of keeping his laws. What Australian can lift his head and ask for rights from God when 80,000 unborn children are deprived of life every year?

We owe God a debt – damages we can never pay. John the Baptist warns us that there will be a great separation, every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cast into the fire. But Jesus speaks of ransom, and that should fill us with hope.

I was struck this week by some words of anguish and hope from the book of Job. Job does not know about resurrection. What he observes is that people die and that is the end of them. No one returns from the grave. But in the midst of his agony he speculates that if such a thing could be, it would cast a different light on his sufferings:

Job 14.14 If a man dies, shall he live again? If that were so then all the days of my bondage I would wait, till my renewal should come. 15 You would call, and I would answer you; you would long for the work of your hands… my transgression would be sealed up in a bag, and you would cover over my iniquity.

You see that in his wishful thinking he sees how important it would be, if people were to come back to life again, that their sins should be covered over. Can guilt be put in a bag and sealed up? Jesus said he had come for just that reason, to give his life as a ransom in place of many. That is our great need and that is the great service he will do us.

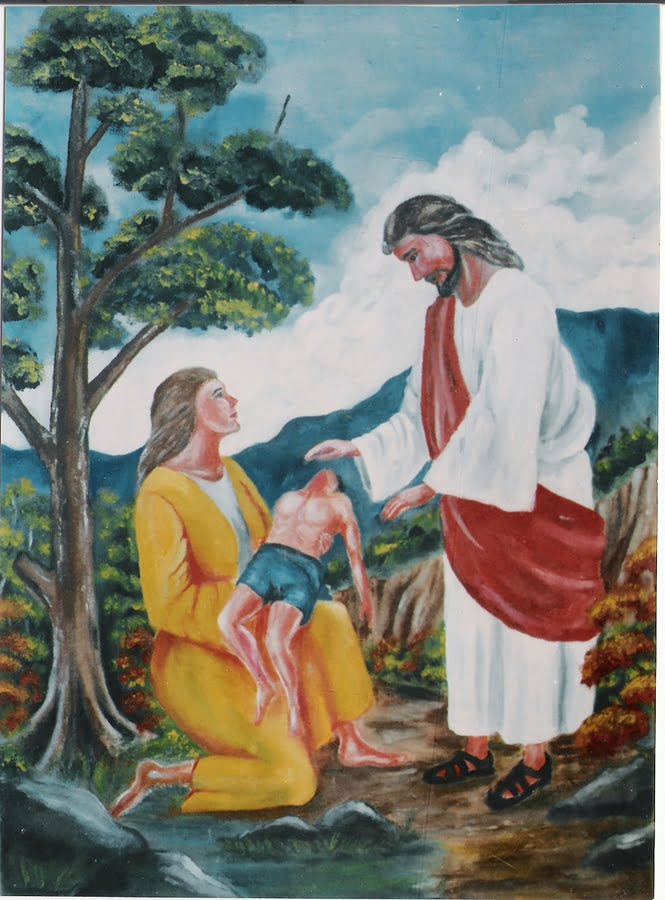

In the story which follows this Jesus heals a blind beggar who sat by the roadside at Jericho. I cant say for sure what was in Mark’s mind when he put these two stories together, but I wonder. Jesus has just made an extraordinary statement about providing a ransom for many. Well, you expect leaders to provide for the many, what you don’t expect is for them to take notice of an individual. In the story of Bartimaeus Jesus notices and extends his mercy to one person, as he wishes to extend his mercy to you.

A big crowd was on its way to Jerusalem expecting to see exciting things, even a coup, and Jesus forming a new government. Hard to hear one person’s voice in the midst of all that – though Bartimaeus could yell; he knew this was the one chance he would ever have to get Jesus’ attention. And Jesus stopped and called him, and listened to his plea for mercy and sight. I don’t imagine Bartimaeus thought he had any rights, that he was thinking he deserved to be healed. If Jesus was God’s man, his one chance was mercy, that Jesus would pity him, and he did. He gave him back his sight and continued the journey with Bartimaeus dancing along behind him. On the day you genuinely call to Jesus to have pity on you he will redeem you from all your guilt and heal you of your spiritual blindness.

What kind of king? That was our question. James and John, the Sons of Thunder, saw and heard it all: the healer, the exorcist, the evangelist, the teacher, the storm-stiller, sea-walker, crowd-feeder, the one who refused to call fire from heaven to revenge himself on a rejecting town, the one who stopped and talked to a beggar and gave him sight – but most of all the one who said he had come to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many. They saw him do it, on the cross, and they spoke to him again when he was alive.

What kind of king?

James or John are perfectly sure of the rightness of calling fire from heaven against a village that closed its doors to the divine king, also of the guilt of the city which is about to oppose him and put him outside its walls and kill him. They are eager to be God’s instruments for that judgement. But the day is fast approaching when they would run for cover and leave Jesus to it, and soon the penny would drop that they are a part of the guilty race themselves. This is what we do not see in these modern followers of Muhammad, and many others: conviction of sin, seeing we are foul of God’s law and approaching a judgement that will exclude us from God’s new world for ever – unless forgiveness is possible, a forgiveness which satisfies the demands of God’s broken law. And that comes only through redemption. The king stood in place of his people and paid their penalty. That was the service Jesus offered to God, and the way he served us, his people. He died in our place, so we can go free. That is what James and John came to see, and it changed them.

John will one day write these words: “If we claim to be without sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness.” (1 John 1.8-9) That is a John who has come a long way from his Son of Thunder days, the outraged righteous one, who wanted to call down fire from heaven on that Samaritan town. He eventually saw that his king was different, and it made him a different man.

John gave himself a new nickname, “the disciple whom Jesus loved.” Becasue service is very closely related to love. Of course, there is service that is done purely out of a sense of duty, and there is service which is forced on us. John experienced Jesus’ service is neither of those, but as love. Later in his life he wrote,

1John 4.7 Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God. 8 Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love. 9 In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him. 10 In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins.

In May this year I spent 10 days in Mozambique. In one of the cities I spent quite a bit of time with the pastor of a large church. He was a fourth generation Muslim. His family owns a mosque. The story of how he and his Muslim wife came to Christ and are now leading the Christians in their city is extraordinary, but too long to tell. Anyway, we were driving to see the site of their new church and I said to him, “It must have been strange for you, a Muslim, when you first faced up to Christianity. What was the thing that was biggest for you?” He didn’t hesitate. “Love,” he said. “I never heard about that in Islam.”

[1] It was written more than 100 years after Muhammad’s career. And it was lost. This translation is a reconstruction based mainly on a later writer who quoted large sections from the book. Ibn Husham wrote about 200 years after Muhammad. How fortunate we are to have the gospels. Mark wrote less than, 30 years after Jesus death and resurrection, when most of those who knew Jesus were still alive.