“We are unworthy to gather up the crumbs that fall under your table.”

Matthew 15.21-28

A sermon preached at St Peter’s Victoria Park 16th August 2020

When I left my home and parents to venture into the world, I very definitely did not believe in Jesus. For about 3 years I had attended church with my mother and served for a while as an altar boy, but what for her was a new faith, had not rubbed off on me. I believed in god and I prayed for things I wanted and that was enough. Jesus complicated things. I couldn’t see the sense of it. Two years later God moved in on me, and forced me into surrender on something I badly wanted; and suddenly Jesus made all the sense in the world. I saw that the god I had believed in was a product of my own imagination – a plasticine god who liked all the things I liked and had all the same opinions as me. My favourite phrase was, “I like to think God is …” My god was an idol. Over that week I saw that God was himself; he wanted things I didn’t want; he was not an image of me. And then suddenly – and it was sudden – I saw that Jesus was the way God had made himself known to us. He is God, become a human being.

I wanted to say that in introduction, because we have just read a troubling story about Jesus, and I want us to begin with the idea in our minds that Jesus is God making himself known to us. If you don’t believe that, you are not yet a Christian, and you will have to put a “what if” above what I am about to say this morning.

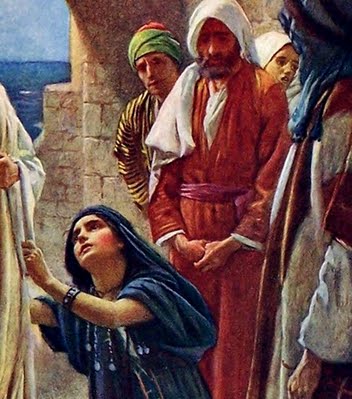

Jesus is outside of Israel: the only time we know that he went beyond the borders of his own country. He is in Lebanon, not too far from where the August 4 explosion would take place. He is approached by a woman, who begs him to help her daughter, who is “badly demonized”. Let’s just say for now she is severely troubled, probably epileptic, maybe more. She thinks, and maybe he does, that it is caused by an evil spirit.

Jesus doesn’t answer her: “not a word”. Matthew explains that she is a Canaanite woman. It’s a surprise if there were still people who were identified as Canaanites; in any case Matthew is marking the fact that she was the lowest form of human life. The Canaanites were under a curse. Israel was commanded to exterminate them when they entered the land God promised to them. They never quite finished the job. There were any number left behind, but there had been no country called Canaan for 1500 years, and there is no evidence of a people-group who called themselves Canaanites. Canaanite carried a stigma with Jews.

Africans are very sensitive to racial stigma – understandably, especially South Africans. In the old apartheid mythology, the settlers pushing north imagined themselves as Israelites, and the blacks as Canaanites. It was a perverse and mistaken example of contextualization: reading yourself into the Bible story.

I had a Congolese student at the college in Cape Town who went as a missionary to Japan. When he returned after a few years, I asked him to speak to the students. Afterwards there were questions and one black student asked him if he had met up with any racism in Japan. “Well, not really,” he said. “Of course, the Japanese think they are the master race, but if you’re English or American or African you’re OK.” And then he added, “But if you’re Korean, you’re dirt.” You run into racial feelings everywhere. Many people like to think they are better than someone else. But with Israel it was far more serious. God had chosen them and commanded them to keep away from the other nations, the “Gentiles”; separateness was part of the law of Moses. If you accept the Old Testament as from God, as Jesus did, and Matthew did, then you accepted that. And “Canaanite” was the worst kind of Gentile. Mind you, they had earned it. When Abraham was in Canaan they weren’t so bad, but when Joshua returned 500 years later, they had bottomed out. Sex was a religion, worship was what you wanted, preferably with lots of sex, and sex of all kinds, idols proliferated, so did necromancy – that’s trying to communicate with the dead, occultism. Child sacrifice was the ultimate form of worship. I mean, the Romans weren’t saints but when they came to Carthage – Carthage was a city in North Africa opposite Italy; the Carthaginians were part of the same civilization as the Canaanites – when the Romans saw what was going on, they were appalled, and burnt the place to the ground. Israel was supposed to do the same. But some survived.

The disciples are distressed, not at the woman’s need, or at Jesus’ political incorrectness, but at her disturbing their peace. They came to Lebanon to escape the crowds and for some peace. “Send her away,” Lord, “she won’t shut up.” It is at that point that Jesus tells them that his mission is to Israel exclusively: “I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel.”

They weren’t in Lebanon on a mission. He wasn’t there to convert people. He was actually escaping from a wave of popularity in Israel and wanting to be alone with his disciples. So, he answered her not a word.

With the “black lives matter” movement in fall cry around us, this is pretty tough stuff; especially, remember, I am saying Jesus is God himself. This seems like quintessential racism: Jewish male privilege in this case! Jesus and twelve men against this one poor, marginalized woman.

But let’s try to see it from God’s viewpoint – and I warn you, this won’t make it easier. We talk a lot about the love of God – and rightly – but it is also true that God is deeply grieved by the human race. Let’s be clear: there is one human race, and only one. People who imagine there are different races are mistaken. We are all one species, from one original set of parents. Colour is a triviality. But the truth is, we have all offended God greatly, to the point of him wishing he had never created us. Despite everything that he has given us, we have turned our backs on him, and persist in misusing and abusing his gifts, and each other. And we are under a curse – not just this Canaanite woman. That is the plain teaching of the Bible. We once had a prime minister who said, “Life wasn’t meant to be easy.” The reaction surprised him. For many Australians this was a strange idea; surely life was meant to be easy, and if the government would only do what it should, it would be easy! But the Bible says God responded to the rebellion of our first parents by cursing the ground so it wouldn’t easily cooperate, and condemning us all to eventual death. A man was preaching in a London church. He was not a clergymen, but is often in the news and is watched by the media. He said in passing in his sermon, “Of course, we know that we are all under a curse.” The next day that was in the London newspapers: such a weird thing for anyone to say! Their English forebears wouldn’t have noticed. It was standard Christian understanding. It is writ large in the Burial Service of 1662. Of course, what has changed is our materialist world view. Death is seen as natural. God has been excluded from his creation.

So, when God called Abraham out from among the runaway idol-worshippers, the world was under a curse. God promised to bless him, and make him a great nation, and bless his descendants, and be their God and they his people. In the end, through Israel’s faithfulness and the blessing they would enjoy, the rest of the world would wake up and turn back to their creator. So, when Abraham’s children multiplied and God found them enslaved in Egypt, they cried out to him – just like this woman: “have mercy on us.” And God rescued them because he had promised Abraham, and made them a nation, and gave them a land – but … to cut a very long story short – the more he blessed them, the more they decided they didn’t need him, and spat in his face worse than the rest of the world. And he was grieved and angry, and said to them, “OK if you don’t want me, you won’t have me, and turned away. And that was not good. They were left to the mercy of the world, and there was no mercy in the world. They were invaded, killed, scattered, enslaved … until once more they saw their stupidity and called to God to help them. And he promised to send them a king, who would liberate them and put things right forever. And that brings us to where we are in our story. Jesus announced the kingdom of God, and for those who had eyes to see, he was the king. He was liberating people and putting things right, in wonderful ways that no one had dreamed of, and who knows where it might have ended. But in other ways he was not what they wanted. So, in the end they turned its back on him and killed him. But that is to jump forward; here in Lebanon, a little south of the blast site, a woman is trailing after him crying out, “Son of David, have mercy on me.”

She is at her wits’ end; her daughter is sick, sick, sick. On Wednesday our daughter gave birth to her third child. I was with her when she had her first. It wouldn’t come. She was demented with the pain. I was pacing the ward. “Lord, have mercy.” I couldn’t keep my mind away from the worst: what if? I can hardly describe my feelings that day. Last week all those feelings came back. Daughters are so precious. If anything happens to them, it is unbearable.

This poor woman is desperate. With pure delight she has carried this child in her body. The pains of birth arrived, but were soon forgotten in the joy of a newborn – nursing it on her breast, watching it develop, learn to laugh, walk, speak – and then whatever it is that came over her: sickness, disfigurement, ugliness, hate, hardly a human being any more: “badly demonized”, her mother describes her. Who knows, maybe attempting to contact dead spirits was part of it. She approaches Jesus, and Matthew says she “worshiped” him. I’m sure she didn’t think he was God, but she bows before him and acknowledges his authority and power. “Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David.” She acknowledges him as “Son of David”, Israel’s promised king. Jesus’ reputation has gone before him. This woman believes he is Messiah. Stories of his healings and other miracles must have travelled a long way north.

She begs him for mercy. “Elieson me, Kurie!” Do you register that: “Kyrie elieson – Lord have mercy!” We will say these words in our service this morning: “Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy, Lord have mercy!”

But he only repeats what he has said to the disciples: “It is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.” If she had any pride, she would have said, “How dare you, you arrogant, racist, male-chauvinist, hate-filled Jew!” And she would stand on her last little bit of dignity and stalk away. But she is desperate, and she is not going to go away, because she believes that the man before her can heal her daughter, and no one else can. And she accepts that she is an outsider, with no claim on the blessings promised to Israel. She accepts she is from a people who, to quote St Paul, are “aliens to Israel’s citizenship, strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope, and without God in the world”. This story is full of surprises. “Yes, Lord …” she says, “I accept that I belong among the dogs and deserve nothing, but “yes” too, you should help me – “for even the dogs eat the scraps which fall from their masters’ table.”

What will Jesus say to that? ….. “Woman, you have great faith. What you ask for you shall have.” And Matthew says her daughter was healed from that very hour.

So, did Jesus heal her under sufferance? That is the question that pushes forward now. We know that cannot be so, because of the way Matthew develops and ends his Gospel. No, what appears on the outside as a chance meeting and a rebuff, is actually what a friend of mine would call “a divine appointment”. According to St Paul – I am quoting from Ephesians 1 – “God chose us in Christ before the creation of the world … and predestined us to be adopted as his sons and daughters.” This means this Canaanite woman was destined to meet Jesus on the road that day, and become a child of God. It means that God had prepared for this before he created the world. And Jesus always did what he saw his Father doing (John 5). God would make her a woman. God would determine that she would be a Canaanite living in Lebanon. (She could have been born a Jew.) God would give her a beautiful child – and here it becomes difficult – yes, and the child would suffer from a terrible illness, and her mother would struggle with it for years, and lose all hope. But then she would hear rumours about Jesus, and learn he was in her district, and God would awaken a glimmer of hope. The rest we know. God said nothing; he often does. God tried to send her away. But God also gave her the faith to believe that the man before her had the power to heal her daughter, and God pressed her on.

What can you and I learn from this encounter between Jesus and this Canaanite woman who would not let go? Firstly, God stands behind all the troubles and trials and sorrows of the human race. It’s not the only thing to say, but it has to be said: “God is the great enemy of mankind.” The setbacks, the disappointments, the droughts, the fires, the floods, the blasts, the wars, the epidemics, the accidents, the cancers – death itself. If we do not face this ultimate truth about our tortured world, and about our own life, we will never come to the peace which passes all understanding.

We read this morning about Joseph. His brothers sold him into slavery, he became a house-servant in Egypt, he was falsely accused and went to prison, he was forgotten by those who should have helped him. For many years it seemed that God was silent. And then everything changed, and in the end, Joseph saw that God was there in it all. “You meant it for evil,” he said to his brothers, “but God meant it for good, to bring about a great salvation for many people.” When we realize that God is the one who has done it to us … either we will hate him, or else … we will see that the one who is causing us to suffer, is the only one who can help us. Then, however reluctantly, we will approach him and beg for mercy.

That will not be easy. All pride must be left behind. We are members of an accursed race; we must accept that. Even if you are a Jew, all the privileges you once had have been forfeited. “Do not think to say to yourself, we are Abraham’s children;” I am quoting John the Baptist. “Abraham is not your father; the Devil is your father;” I am quoting Jesus. “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God;” I am quoting St Paul. As for us Gentiles, we also come just as that Canaanite woman came. And if we come thinking we have any goodness of our own that deserves consideration … God remains silent. In our communion service we will also say, “We are not worthy to gather up the crumbs under your table …” Where do you think Cranmer got that idea?

But if we come in our desperation, in our great need – and we all are in great need, for all of us must face death, and we all must face God’s judgement – the prayer goes on: “We are not worthy to gather up the crumbs under your table, but you are the same Lord whose nature is always to have mercy…” Jesus said, “Come to me, all who labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” He also said, “I am the bread of life; whoever comes to me will never go hungry and whoever believes in me will never thirst.” And again he said, “My Father’s will is that everyone who looks to the Son and believes in him shall have eternal life and I will raise him up at the last day.”

If we truly come to him, we will know the joy that we have been accepted, and captured by that everlasting Love, that has driven us low, but only that he might find us, and lift us out of the mire, and set our feet on the rock.

Like Rahab the harlot, the Canaanite woman found God, found the promised king, found the Saviour, found eternal life. Matthew will go on to tell the rest of Jesus’ story, and how the Jesus who said, “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel,” died, and rose, and commanded his disciples, “Go and make disciples of all nations all nations – baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, teaching them to obey everything I have commanded, and remember, I will be with you for ever.” But that is for another time.